On Sunday evening, Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) acquiesced to reality. He was running for president in the way that so many people run for president, coasting on a “ya never know” vibe while computer servers sent out thousands of emails begging Americans to charge $5 to their credit cards at a fundraising site.

But anyone who pays even a slight amount of attention to American politics did know, as almost certainly did Scott. And if Scott didn’t know before Sunday evening, someone at least successfully impressed that knowledge upon him and he realized that he was not going to be his party’s presidential nominee in 2024. (The servers, joining much of Scott’s staff in not being aware of what was coming, kept churning out those emails to the last.)

Instead, the Republican nominee for president in 2024 is likely to be Donald Trump unless something astonishingly bizarre occurs. It’s a reality that was further impressed upon me when I embarked on an effort to rethink how I looked at presidential primary contests.

For the past few weeks, University of Wisconsin at Madison political science professor Barry Burden had been depicting the size of the GOP primary field by plotting the time until the Iowa caucuses against the number of candidates still in the race. The resulting effect is a sort of a bell curve, with the field already well into the downslope.

Burden’s chart made me want to create my own version, so I did. I have compiled entrance/withdrawal dates for primary fields stretching back more than 20 years, so I compiled similar versions of the bell curve using that data. Instead of simply showing the size of the field, though, I wanted to show when individuals joined and left the race, to get a more detailed sense of the ebb and flow.

This was the result, with the vertical axis indicating the size of the field.

There’s a lot of information there. You can see, for example, that the number of candidates tends to rise rapidly and winnow more slowly. You can also see that Iowa used to be more of a tipping point; in recent contests — in part thanks to the increased number of candidates — more candidates dropped out before those caucuses.

What struck me most, though, was how much the 2024 Republican field looks like the 2016 Democratic one. You have the favorite jumping in early — Trump and Hillary Clinton, respectively — in part to box out the field. The field grows (more this year than in that one) and wanes before Iowa arrives. The earliest entries to the contest stuck around longer.

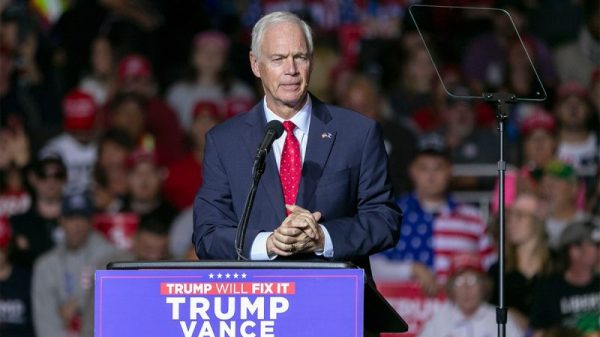

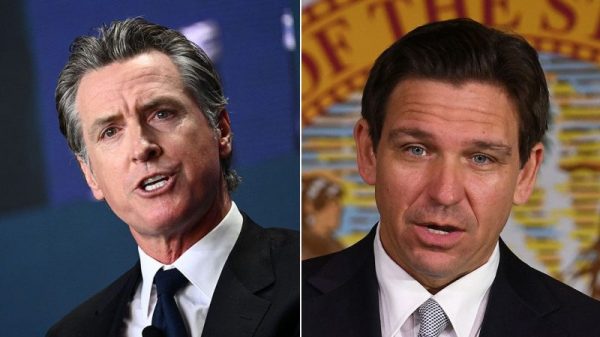

When Clinton launched her 2016 campaign, though, she did so from a much more robust position. Trump’s announcement a year ago came at a relatively low point in his support among Republicans; he took a lot of blame for his party’s underperformance in the midterm elections, which provided some room for Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R). When Clinton’s 2016 campaign began, she was well ahead of any other contender, not that there were many.

By a few months before Iowa, though, one had emerged: Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.). His campaign launch in April 2015 slowly built support, most heavily from younger voters. By the point in the 2016 cycle where the 2024 field now finds itself, Sanders had surged to about 30 percent of the vote. From then until the Iowa caucuses, that support grew as Clinton’s fell.

That’s not what happened to Trump in the 2016 cycle, certainly. By this same point relative to Iowa, he was the front-runner, but not overwhelmingly. It was a large field, and support was splintered. His lead solidified as the caucuses neared, but he wasn’t doing much better than Sanders.

This year is very different. Trump has a substantial national lead, according to 538’s average of polls, larger than any he enjoyed in 2016. DeSantis remains the second-place contender, but his position is much weaker than it was at the beginning of the year. He is by no means gaining ground on Trump; if anyone is, it’s Nikki Haley, former ambassador to the United Nations. But even Haley isn’t gaining much.

One might be tempted to look at the 2016 Democratic race and see that Clinton’s lead was almost completely eroded by early 2016. But that ignores that Sanders’s growth was slow and steady during 2015, which DeSantis’s and, for the most part, Haley’s haven’t been. For those looking for signs that Trump might stumble, there’s another word of caution: Clinton eventually locked up the nomination fairly easily.

Of course, she then went on to lose the general election, an unpopular candidate facing off against a similarly unpopular candidate from the other party. Trump will be in the same position next year, it seems safe to assume — with President Biden playing the role for Trump that Trump played for Clinton seven years ago.