On Sunday, NBC News released a new national poll of the 2024 election that, in another context, would have been a political earthquake of unprecedented scale. Instead, it was an aftershock.

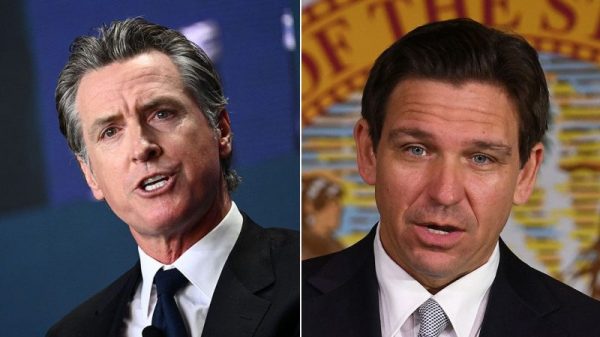

The network’s pollsters called Americans to ask them their choice in a hypothetical — but increasingly probable — election between President Biden and Donald Trump. Trump held a narrow edge, within the margin of error, but outperforming where polls stood shortly before the November 2020 election featuring the same candidates.

What triggered Richter measurements, though, was the result among young voters, those under age 35. They not only didn’t give Biden a substantial edge, as they had in 2020, but they also offered a narrow advantage to Trump. Again, within the margin of error, but that’s a bit like discovering thieves stole all but $5 from your bank account — not much consolation for the president’s reelection team.

This is a remarkable finding — but also one that’s in line with other recent polling. A national poll conducted by Siena College for the New York Times in six battleground states found Trump and Biden running even with the youngest voting bloc. So did polling from CNN and Fox News. This has cropped up repeatedly over the past few weeks, prompting a lot of correct-but-coping mutterings about the reliability of polling a year before an election in which the final candidates aren’t even set.

The Financial Times’s John Burn-Murdoch had an interesting observation about this: Biden seems to fare worse with younger voters in polls conducted by phone (including cellphones) rather than online. Recent YouGov polling, conducted for the Economist, shows an example of it: Biden has an 18-point edge with those under 30.

But this isn’t as clear-cut as it may seem. Quinnipiac University’s phone-based poll showed Biden with a bigger advantage than others using the same methodology. Working in the other direction, as The Washington Post’s polling director Scott Clement pointed out, respondents to the Siena-Times poll in the youngest age group indicated that they voted for Biden by a 22-point margin in 2020, in line with post-election estimates for that age group. That suggests a shift in views, not simply a fluke of methodology.

So let’s take a step back and consider why those positions might have shifted — and why, as Burn-Murdoch notes, support for Biden among Black and Hispanic voters has similarly seemed to soften in recent polls.

One can point to a lot of recent triggers for Biden’s erosion of support. But this isn’t simply a new phenomenon, related, for example, to opposition to Biden’s response to the Israel-Gaza war. In April 2022, we noted that Biden’s approval rating had fallen the most among the youngest Americans, in part because they were higher in the first place. This trend has been measurable for a while.

It’s worth remembering that there is a substantial overlap between three groups: non-White Americans, political independents and young people. Young people are much more likely to be registered as independents than are older Americans — and, in fact, are more likely to be registered as independent than as members of either party. It’s also a much more diverse group of people than older Americans, who are predominantly White in part because many of them (including baby boomers) were born and raised during a period of legally restricted immigration.

That high rate of registration as political independents overlaps with a decline in participation in other institutions: church, marriage, labor unions, the military. It also correlates to skepticism about institutions. In the aforementioned CNN poll, those under 35 and independents were the most likely to say that there weren’t significant differences between the two major parties (though a majority said there were).

In the abstract, this indifference to institutions is unsurprising. That’s partly because young people are young and institutional participation or loyalty is often something that accrues over time. It’s also partly because we’re talking about a generation of individuals raised in the age of internet ubiquity, of employment that’s often contingent and a social environment centered heavily on individual identity. It’s extremely easy to overgeneralize here, admittedly, but gig employment (as the phrasing has it) is more common among younger Americans. As is registering as a political independent, of course.

This decline in institutional participation has other likely ramifications. Burn-Murdoch noted that young Black men in particular seem less willing to support Biden. Young Black people are also less likely to attend predominantly Black religious congregations, a place where, as analyst David Shor pointed out to me a few years ago, social and political identities are reinforced.

Biden’s initial candidacy and subsequent presidency have been heavily centered on bolstering institutions, in part as a response to Trump’s term in office. But he also needs the Democratic Party and Democrats to stand with him because he is the party’s presumptive 2024 nominee. He needs to bank that institutional support — but young people have shown little such loyalty. Though they are ideologically to the left, benefiting Democrats in other elections, like the 2022 midterms, there doesn’t appear to be loyalty to Biden simply for being the Democrat on the ticket. I mean, they’re often independent! But even the partisans haven’t been voting Democratic for decades, the sort of institutional habit that parties need.

Political scientist Julia Azari said it best: We’re in an era of weak parties and strong partisanship. That is probably working heavily against Biden as an older, moderate, institutional candidate when considered by progressive, young, independent voters.

I’m at risk here of absolving Biden of any culpability. It’s clear that his problem isn’t only institutional. A fifth of Democrats in the NBC poll said they disapproved of his presidency. He has significant challenges that extend beyond this sort of abstract consideration of the polls. But it also means that he may have a lower floor than he would like, with even people who back Democrats being willing to jump ship or stay home.

It’s early. Things change. And there is still the chance that the issue here is to some extent derived from the antipathy of younger people toward answering their phones. But that, too, speaks to the overall thesis: The institution of opinion polling had to adapt to people who don’t comport with its expectations.

Institutions of all kinds are scrambling — words written for The Post and being read, almost certainly, by an audience that has relatively little overlap with the subject of this article.